The following piece was written by my colleague and contributing author Andrew Willner, a sustainability advocate and sailor in the NY/NJ area of long standing. I am pleased to be actively working in partnership with Andrew this year and to share his observations on the blog. –Erik Andrus

In a January 2014 on my blog I talked about the choices this old “sailor” was considering as I looked at 70. In that piece I wrote about my interest in the Vermont Sail Freight Project, “the Vermont Sail Freight Project is the furthest along of these ideas. Founded and implemented by Erik Andrus a farmer in Ferrisburgh, VT. VSFP is a slow tech approach to energy and a resilient food system.

Erik has said about the project, “The Vermont Sail Freight Project originated out of our farm’s commitment to resilient food systems. Producing food sustainably is not enough. The other half is sustainable transport of goods to market and equitable exchange. A good portion of the damage conventional agriculture does to society and the environment is through our overblown, corporation-dominated distribution systems. The idea of a small, producer-owned craft sailing goods to market, perhaps even a distant market, is an alternative to this system, and one which has served our region well in the past. “

I signed on in significant part because Ceres, Erik, and the crew confirm my belief in preserving the skills of the past to serve the future. The Vermont Sail Freight Project appealed to my head and heart in significant part because I agreed with Erik when he said to a member of a television crew, “I offered my belief that contrary to the techno-paradise that some expect, my belief is that our future will likely resemble our past, and that we may fall back on proven, low energy approaches to supporting human life that have been historically proven to work. “Isn’t that pessimistic?” asked the interviewer. I replied that I don’t think so. It is in my view even more pessimistic to imagine a world continuing on the current path, becoming a place in which there is no place for human labor or creativity, where rather than doing things with our backs and hands and minds, we must instead wait passively for conveniences and solutions to be marketed to us. That, to me, is the most depressing future imaginable.”

The adventure started when I picked up Captain Steve Schwartz on my way to Vermont. I met Steve briefly late last summer before Ceres’ first trip, and we exchanged emails when he learned that I was going to be a crew member. We talked constantly all the way from the Hudson Valley to Erik’s farm. It turns out we are close enough in age to share musical taste and Vietnam War draft board experiences. (Maybe I will do another post about this to the tune of Alice’s Restaurant).

We also have Hudson and Harbor stories and friends in common from Steve’s long term commitment to Clearwater as Captain of the Sloop Woody Guthrie, to his friendship with and my appreciation of the work and life of Pete Seeger, from my days as mate on theSchooner Pioneer, and because of the people I met during my 20 years on the water in the Harbor and lower Hudson as the NY/NJ Baykeeper.

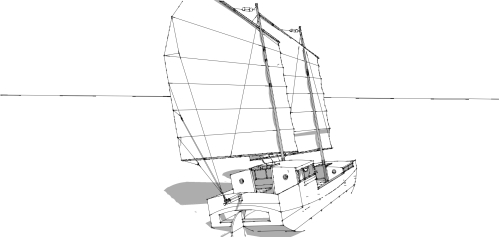

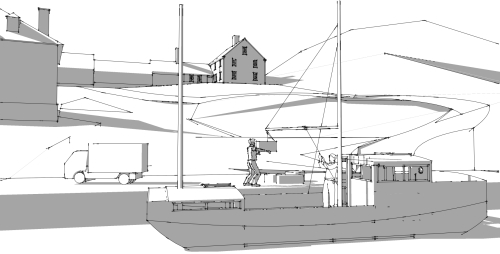

The next few days were an amazing ballet (or rugby scrum depending on your point of view) of riggers adding a topsail and outer jib, food shopping for a crew of four, moving and loading the cargo totes, trading one ailing outboard for a used but working one, deciding on last minute changes to the schedule, loading on personal gear, and finally getting underway.

But more than that I learned firsthand why Erik is so passionate about this project. One of the reasons he asked me to help out for a few critical weeks was because he was in the middle of planting rice in a “paddy” that he had constructed in a low lying part of his farm. It was eye opening to see what goes into the preparation and planting of this specialty northern variety.

He was also up early baking bread, for sale at a nearby farmers market from local grains in the wood fired oven that he had built. Erik’s quest for resilient food became more apparent as I saw the dedication to local production and distribution that the bakery epitomized and that the care that went into the preparation of the muddy field for the rice.

It was also apparent that he put the same kind of thoughtfulness and consideration (and appropriate business model) into buying the local shelf stable products outright from neighboring farmers. The cargo of mostly Vermont maple syrup, honey, preserves, cider syrup, “fire” cider, herbal teas, grains, flour, and beans meant cash in the pocket at a time when many farmers are strapped.

I watched from land as Ceres left the town dock in Vergennes, turned down stream just under the falls and disappeared around the bend in Otter Creek on the way to the Lake. Ceres and her crew, Captain Steve, Meade Atkeson, and Matt Horgan spent the first night anchored in one of the most beautiful shorelines on Lake Champlain, Button Bay just off the State Park. The next morning Erik rejoined the boat along with Edward and Gary from the French television program Thalassa for the trip down the Lake. I was not on board (that’s a whole other story), but. I was fortunate to stand on a bluff above the bay and able to watch the boat get underway, and raise all sail for what proved to be an amazing downwind “sleigh ride,” shaking out the new topsail that Steve described as a “turbocharger.”

I caught up with the boat at Whitehall, NY. Whitehall is like a town encased in amber. Its nineteenth century brick buildings face the canal, many empty and waiting for the resurgence of canal traffic to reanimate this once thriving town. It was at Whitehall that we took the rig down (with the boat’s own gear) for the canal passage. We spent the evening in a waterfront bar, as sailors should, and got underway through the first of ten locks the next morning. This was my first trip through the canal, and the only other lock I had been through was the one connecting Lake Union to the Puget Sound in Seattle. Steve was a veteran of last year’s trip and drilled the crew on handling the boat through the locks.

The Champlain Canal is a 60 miles long. It connects the south end of Lake Champlain, to the Hudson River. It was built at the same time as the Erie Canal and was completed and opened in 1823 from Fort Edward to Lake Champlain. The canal carried commercial traffic until the 1970’s. Today, except for the tugs, crew boats, dredges, and barges connected to the General Electric PCB clean up, most of the traffic is recreational boats that can travel up Lake Champlain to the Chambly Canal that connects the Lake to the Saint Lawrence Seaway.

It rained almost every day of the transit, and the thing about foul weather gear, even the new “high tech” stuff is that you sweat, so you are almost as wet at the end of the day as if you hadn’t worn anything at all. But that didn’t stop all aboard from being astounded by the canal. The trip through the locks was eye-opening and the 19th century technology (with some 20th century updates) is a credit to the ingenuity of the engineers and builders. The lock tenders for the most part were friendly and supportive while the always gregarious Captain Steve renewed friendships from the previous voyage and made new friends. These relationships were important as the tug, barge and crew boat traffic is very heavy, and our small vessel and its crew were treated with professional courtesy, and once in a while even given hints about where there might be a place to spend the night near electricity and water.

We did a quick stop in Mechanicville where Pete Bardunias from the Southern Saratoga Chamber of Commerce, (a long time supporter of the project) brought local dignitaries and some vendors to the newly rebuilt town dock. We took on some cargo from local preserve and herbal tea businesses to sell down river. A local newspaper covered the arrival and like last year the project got some amazing press.

Our next stop was Waterford where we thought we might spend the night but then forged on to Troy. Troy was an excellent stop especially because the dock is just steps from Brown’s Brewing Company , where, if I hadn’t already learned that Steve was a beer connoisseur (I guess I should have known since half of his gear he packed in my car was artisanal home brew), I knew by the end of a well deserved meal and brew in a nice dry pub. Eric the dock master at Troy was elated that Ceres would be doing a market on the way back north, and said he would spread the word among the many advocates for the Project in Troy.

We raised the rig at Troy and then partially dipped it to get under the Troy/Albany lift bridges and then lifted it all the way back up and sorted out the rig, practicing raising and lowering the sails, but mostly motored through foul currents and a bad rain storm. This was the part of the trip that a transformation began to happen, four people of different ages, backgrounds, and experience began to become a crew. Only people who have spent time on a small vessel for a length of time understand the mysterious way it happens. Maybe it is called teamwork, but I believe it goes beyond that. On a boat, each person has a job to do, but that job is entirely dependent on others doing theirs, and intuitively knowing when someone needs assistance. It is also about shared “hardship.” There is nothing much fun about being so busy that breakfast lunch and dinner are all peanut butter and jelly on day old bread, or leaks over your bunk, or sores on your hands from handling wet coarse manila lines.

But it goes beyond bunker mentality, you share chores, share stories, find commonality, begin to make friends, and that is when the crew and the boat become a working whole. There is nothing in the world like the feeling of a sailing vessel, trimmed right, crew at their stations, a fair wind off the quarter, heeled slightly, sails full, a telltale vibration in the tiller, smiling, and thinking, “this is the most fun I have ever had standing up.”

We anchored just south of Saugerties after a passage through an unmarked, “local knowledge” channel where the crew was afforded great courtesy at the home of one of Steve’s friends “Doc” and his extended river family. Not only was it good to sit in a dry house, but the food and company was good as well. The anchorage was remarkably beautiful and serene. For those who have not had the experience or treat of sleeping aboard a boat in a safe anchorage, with the sound of water lapping on the hull lulling you to sleep, it is impossible to describe the peacefulness. However, as old men do, I was up in the middle of the night, and by habit, checking to make sure the anchor hadn’t dragged, looking at the stars, seeing the reflection of lights on the water from the far shore, and tired again, going down below, and back to bed.Next morning we took on a guest, Chris O’Reilly, who is a shipwright, rigger and Clearwater crew member. With a fair wind and current we raised sails and made two quick stops. We dropped Chris off at Rhinecliff, and then sailed down to Poughkeepsie where we picked up Meade after his weekend back at school, finally we continued our downwind charge including the “turbocharger” topsail.

It was at this point that I started to learn a few hard lessons:

- I didn’t remember as much as I thought from my days of being the mate and captain of traditional sailing vessels since that had been more than 20 years ago.

- Despite that experience I was not the captain, or even the mate, but a deck hand,

- That 70 year old deck hands have trouble keeping up with 20 something deck hands.

- That I was having fun despite the hard work and wet weather,

- And that this unlikely boat when trimmed well and sailed skillfully would go to windward.

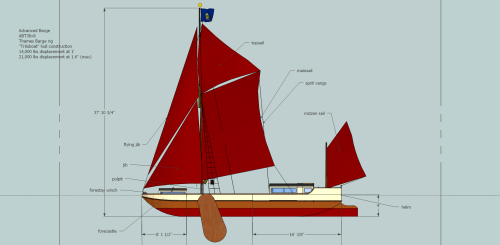

Below Chelsea we began to tack to windward using the lee boards. Steve kept experimenting to see how well she could do and drilled us in tacking, finally taking the Yankee down because it wasn’t doing as much as when sailing down wind. We made some down river progress on close reaches and the current, and used the old trick of “backing the jib” to get the bow around.

We got into Beacon that afternoon. The next morning Matt and Meade set up our first market at the Beacon Farmers Market. This was the first test of the tote system, and the bar code inventory. The market went very well and Ceres was a hit. At times during the day there was line at the market stall and at the boat with people wanting to know about the products and the “why” and “how” of the project.

We stayed in Beacon for a couple of days, and then got underway, raised all sails except Yankee and tacked upwind again for a short sail to deliver an order to the Cold Spring General Store at the public dock. People started to gather at the dock to admire the boat and watch cargo being transferred from hand to hand right from the hold into the arms of the store owner. We made more good friends and by the time we were ready to cast off there were so many people on the quay that if we were set up to do so we could have done a “pop up” market. We arranged on the spot to do a July 4th market with the owners of the Cold Spring General Store. After leaving Cold Spring we continued sailing until we were in sight of the Mid-Hudson Bridge.

That evening we anchored and spent the night on the northern edge of Iona Island. There is something pretty astonishing about watching the sun pass behind Bear Mountain, and watch the lights of the commercial traffic as we sat on deck having out dinner. The next morning we sailed off the anchor, and sail/drifted until the current turned and we motored to the bulkhead at the Clearwater Festival site to familiarize the crew about where the boat would be the next weekend.

We arrived at Ossining early afternoon checked in with dock master and the Ferry Sloop contact, found the showers and then the bar. The Yacht Club folks and especially the Ferry Sloop members were helpful and even took me for a needed grocery and hardware store run. The next day we set up a market at the club house of the Shattemuc Yacht Club and drew a pretty big crowd. That evening Steve and I gave a slide show and talk about the project and this year’s voyage to about 25 people.

Ossining Mayor, William Hanaurer came down to the boat at least twice. He said that he wants to make the Hudson Ossining’s front yard not its backyard. He is also advocating for the use of a new public dock adjacent to the Ferry dock for vessels like Ceres. The next day Erik arrived and I reluctantly headed home.

In retrospect, I had a terrific time. It has been a while since I did so much physical work, thought about tide and wind, learning the boat’s gear, assessing its sailing ability, and as observing and participating as much as I could in cargo handling and the marketing. It didn’t hurt that Steve is an experienced mariner and a terrific teacher. I observed that he was instructing the crew as he is learning about the boat’s ability. He is both willing to

press the vessel to see how the gear holds up, but is conservative and prudent when it comes to boat handling. Mat and Meade are terrific young men and great crew. Under trying circumstances they figured out the marketing while learning how to be crew members.

I agree with Erik when he says, “running the vessel and its market requires skilled operators and solid river sailor, plus business capability to maintain inventory and accounts while on the move. It also requires a serious interest in the farms and waterfront communities of the region, and some facility at outreach and social media.”

My take away is while crowded for a crew of four, two to three, friends, a married couple, or partners, could live aboard for the season. I see this second voyage as “proof of concept.” Ultimate success of the project is not necessarily measured by whether it is profitable or not (although I believe it will be). Ultimate success is that in some small way lay the groundwork for the development of the next generation of watermen and women while building an alternative carbon neutral logistic chain, from farmer, to processor, and finally to individual, wholesale, or restaurant customers.

The use of sailing vessels as transportation is nothing new. Many coastal schooners and sailing vessels are still working in the trade between main ports and remote islands and harbors in Africa, Caribbean, South America, The Indian, Ocean and the Pacific. From Northern Ireland to Fiji, freight carrying sailing ships are being planned, built, and sailing. These first forays into what will become a huge post carbon enterprise are examples of how coastal short sea shipping along the North American coasts, bays, and rivers will be changing in the near and mid-term. Some operating and soon to be operating examples are, the Gundalow Company in New Hampshire, Farm Boat in Seattle, Dragonfly Sail Transport in Michigan, while SV Kwai, Tres Hombres Packet Company, Greenheart, andB9 Shipping are ocean crossing sail transport vessels in various states of implementation.

Ceres is now an integral part of this world-wide effort of sail freighters who have started a revolutionary movement to prepare for a carbon constrained world by preserving the skills of the past; marlinspike seamanship, building, rigging, and sailing traditional vessels, developing an alternative logistic chain, linking the farm to the table, participating in “fair trade,” and providing real world examples of what happens when you stop talking and start doing.

This movement is led in part by Jan Lundberg’s Sail Transport Network . Jan said, as long ago as 2007, “Sail power is more than some theoretical future mini-substitute for today’s oil-based trade and flying and driving. The Sail Transport Network’s team is growing, dedicated, talented and well informed about energy and environmental issues — and we love adventure and accept risk. You’re welcome to not just watch but help bring about a better reality for sustainable transport all the sooner.”

Based on my limited experience, I am more comfortable than ever before that the Vermont Sail Freight Project is a timely, doable, and potentially a profitable enterprise. If I wasn’t before, I am now a convert. I am off the boat now, but I think my adventure is just beginning.